“When We Explain the Facts, We Should Also Explain How Misinformation Can Distort Our Facts”

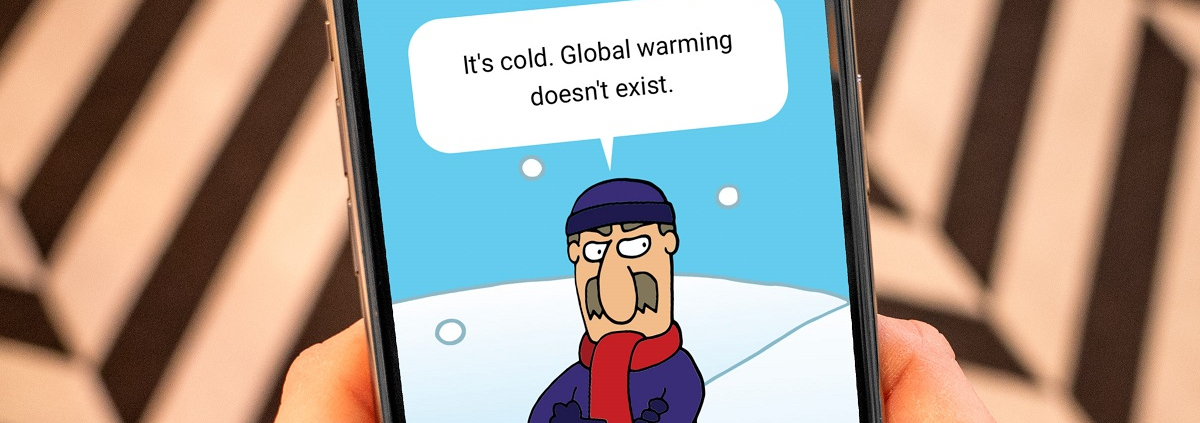

Dr John Cook (Monash University) is an award-winning scientist and cartoonist who fights climate misinformation with humour and critical thinking. He is also the creative mind behind the Cranky Uncle, a “male, older, white, and politically conservative” caricature of those who are dismissive of climate science according to psychological research. His acclaimed book “Cranky Uncle vs. Climate Change” and game app expose misleading techniques of science denial and offer tools to build public resilience against misinformation. His work has not only been used in schools, but he has recently developed a project to counter climate disinformation with Facebook, jointly with other researchers.

He will be one of the contributors to the workshop “Using experiments to fight science disinformation online: an evidence-based guide” at the Future of Science Communication Conference organised by ALLEA and Wissenschaft im Dialog on 24-25 June. Ahead of this conference, he offers some tips and insights on how to combat misinformation in the science communication and education fields.

Question: “Cranky Uncle vs Climate Change” is the name of your book and the game you developed which brings together climate science and dealing with misinformation. Where does this name come from and what is your tip as a first step to dealing with a “cranky uncle” in our real personal lives?

John Cook: Psychological research finds that people who are dismissive of climate science are more likely to be male, older, white, and politically conservative. Cranky Uncle is the embodiment of that demographic type. And anecdotally, almost everyone has a family member, friend or colleague who captures that “cranky uncle” personality type. My first tip in dealing with your own cranky uncle is to recognise that the odds of actually changing their mind is very small, so don’t get frustrated if you don’t make much headway in your conversations. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t engage with them however. Often the beneficiaries of such conversations are not our cranky uncle but everyone else witnessing the exchange. That’s the purpose of the Cranky Uncle book and game – not necessarily changing our cranky uncle’s mind but inoculating everyone else against his misinformation.

“The purpose of the Cranky Uncle book and game is not necessarily changing our cranky uncle’s mind but inoculating everyone else against his misinformation”.

Q.: You wrote a paper on “which counters misinformation better: facts or logic?” concluding that logic outperformed facts in your study. How can we translate these findings for practitioners of science communication?

J.C.: The key thing that science communicators need to realise is facts are vulnerable to being cancelled out by misinformation. When people are confronted with conflicting pieces of information and they have no way of resolving the conflict, the risk is they disengage and don’t internalize our factual explanation. Our research found that if we explain the facts to people then they afterwards encounter misinformation casting doubt on the facts, the misinformation cancels out the facts. However, logic-based corrections that explain how the misinformation misleads is not vulnerable in the same way – the positive effect from logic-based corrections are not affected by misinformation. What I recommend is when we explain the facts, we also explain how misinformation can distort our facts. This is like wrapping bubble wrap around our facts to keep them safe as we send them out into a world filled with misinformation.

“If we explain the facts to people then they afterwards encounter misinformation casting doubt on the facts, the misinformation cancels out the facts.”

Q.: The Cranky Uncle game has found users all over the world, but can it be used equally effectively everywhere, or can cultural differences in communication and science communication influence how to handle misinformation?

J.C.: Currently the Cranky Uncle game is only available in English so obviously that does make it less relevant to the non-English speaking world. Even so, I was surprised to see the game being picked up in a number of European countries and hope to see that trend increase once the game is available in other languages. We are currently in the process of translating the game into German – our first test of the translation procedure. Once that process is worked out, we’ll begin translating into other languages (we’ve had volunteers approach us to translate the game into around a dozen languages and more volunteers are always welcome). There are some language difficulties in translating parts of the game from English. For example, we talk about the ambiguity fallacy, where words with double meanings can be exploited in order to mislead people. Unfortunately, words with double meanings vary across different languages so we’ve been exploring creative ways to tackle this issue. We’ve also discussed adding new cartoons for new languages. For example, a cartoon of Neal deGrasse Tyson features in the current game, as an example of a famous astrophysicist from the United States. We’re exploring incorporating the German equivalent of Neal deGrasse Tyson – an astrophysicist who is well-known in Germany.

Q.: For our Future of Science Communication Conference, we have also focused on battling science disinformation. Have you observed any trends in SciComm practice in recent years which have been particularly successful?

J.C.: The approach of using technology – particularly digital games – has exploded in recent years. Misinformation is nimble and adapts to new technologies and online platforms with disturbing rapidity. That means that science communicators need to be adaptive and innovative in our responses to misinformation. We’re dealing with a complex, ubiquitious problem which requires interdisciplinary solutions that can scale up to meet the huge challenge. Scientists need to be working with practitioners in other fields such as game and app development to develop technological solutions that can reach large proportions of the public. I am excited to see that this is already happening with a number of clever and engaging digital games springing up in response to the problem of misinformation.

“Misinformation is nimble and adapts to new technologies and online platforms with disturbing rapidity. That means that science communicators need to be adaptive and innovative in our responses to misinformation.”

Q.: You recently published a teachers’ guide for your game, and in the past you have authored textbooks for university students on climate change facts and denial. What have you learned from teachers who use your game in their classroom?

J.C.: It was enthusiasm from educators early in the game development that made me realize the classroom would likely be the venue where the game would make its biggest impact. Teachers are crying out for interactive resources that engage their students while strengthening their critical thinking skills. The other thing that struck me in my interaction with teachers has been their creativity in combining the Cranky Uncle game with classroom activities. One example is a delightful classroom assignment where students were assigned to write an email to their teacher, explaining using multiple logical fallacies why the teacher shouldn’t fail the student despite the fact that they hadn’t studied. This assignment is an elegant example of active inoculation, where students get inoculated against misleading fallacies by learning how to use the techniques of science denial. It is also an excellent opportunity for the students to practise humour and creativity, with some hilarious assignments!

“Teachers are crying out for interactive resources that engage their students while strengthening their critical thinking skills.”

Q.: Schools, universities, teachers seem to be natural partners to tackle science misinformation. In your experience, are they willing to join this “fight”? Is there enough understanding of the problem and/or resources to do this?

J.C.: On the one hand, a number of schools and universities have eagerly embraced the opportunity to teach critical thinking and build resilience against misinformation. On the other hand, there are many more schools and teachers that are already so time-crunched, they struggle to fit extra content into their classes. It is important that more resources be developed that make it easier for teachers to incorporate these kinds of activities in their classes, while meeting their curriculum requirements. We also need to build awareness among educators of the powerful benefits of “misconception-based learning” (also known as agnotology-based learning) – teaching students by directly addressing misconceptions and misinformation. This doesn’t need to be seen as negative or combative – rather, it’s an opportunity to combine the teaching of facts with critical thinking (or from a psychological perspective, combining fact-based and logic-based communication). This type of education shows stronger learning gains which last longer than standard lessons – it’s a powerful form of education.

“We need to build awareness among educators of the powerful benefits of “misconception-based learning” (also known as agnotology-based learning) – teaching students by directly addressing misconceptions and misinformation.”