“Climate Action is Slow for a Combination of Understandable Reasons”

Professor Philip Kitcher (London, 1947) is John Dewey Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Columbia University, New York. He is a mathematician, historian and philosopher by training, and he is regarded as one of the leading figures in the field of philosophy of science today.

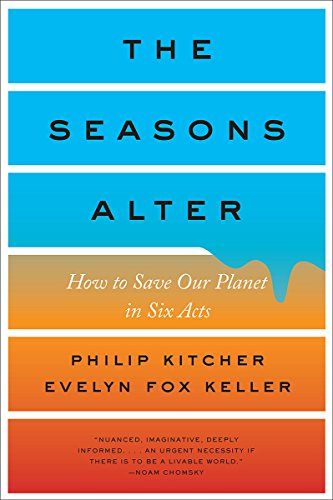

He has authored over 15 books on topics including evolution, epistemology, pragmatism, and secular humanism. His 2017 book ‘The Seasons Alter: How to Save Our Planet in Six Acts’, co-authored with Evelyn Fox Keller, has been characterised as a “landmark work of environmental philosophy that seeks to transform the debate about climate change”, presenting the realities of global warming through a human-centered narrative to better assimilate the science of climate change and its very real implications for human beings.

On 2 November 2021, Professor Kitcher delivered a lecture titled ‘Why Is Climate Action So Hard?’ as part of the PERITIA Lectures Series ‘[Un]Truths: Trust in an Age of Disinformation’. His lecture took place virtually as part of the Berlin Science Week. You can watch it here.

—

Question: What do you think is the role of philosophy in the conversation about climate change, and how do you think philosophers can contribute more to this critical conversation?

Philip Kitcher: Philosophers have done some truly outstanding work on climate modelling, posing and addressing the kinds of methodological questions that are the bread-and-butter of philosophy of science. Our discipline has contributed much less to the other issues that arise about climate change, and that is something that ought to be remedied.

The most basic work philosophers can do consists in offering a structure for the full range of disputes. Evelyn Keller and I tried to do that, by considering six major questions that need to be taken up in sequence. After that we attempted to organise the discussion of each of them, thinking first about framing questions about the evidence for global heating, second about how to assess the impact, third about our obligations to future generations, fourth about how to evaluate the economic consequences of various plans for assuring our descendants a manageable future, fifth about how to answer the legitimate demands of developing nations, and finally sixth, about the transnational democracy that we seem to need (and lack). There are aspects of all these issues that require philosophical treatment.

Q.: Climate action – particularly on the part of policy makers – has been far slower than we need it to be, even in countries where the reality of climate change is not widely contested, and even as climate change scepticism is waning overall. What can philosophy tell us about our apparent inability (or reluctance) to think and act in our own (and the planet’s) long-term best interest?

P.K.: Climate action is slow for a combination of understandable reasons. First, there are large numbers of vulnerable people, in every country, including the affluent world. These people worry that their already precarious lives will be devastated by the kinds of things young activists clamour for. Young people are right to ask for attention to the future but, since they haven’t yet committed themselves to a definite place in society, they do not worry about large changes that might impoverish older generations, or leave middle-aged people without a means to support themselves. Second, the problem of assessing the various kinds of futures that might emerge from the different proposals for limiting the rise in temperature is extremely hard. It is probabilistic in character, and we can’t give serious estimates of any number of important probabilities. Hence, lots of fearful people understandably don’t want to see radical change, because they can hope that things will turn out well even if little is done now. My PERITIA Lecture elaborates on this predicament in much more detail, and (I hope) it shows more clearly how philosophy can contribute.

“Young people are right to ask for attention to the future but, since they haven’t yet committed themselves to a definite place in society, they do not worry about large changes that might impoverish older generations”

Q.: Your 2017 book ‘The Seasons Alter’ is in part an attempt to present the realities of global warming in a digestible way for the general public to understand the science and politics of climate change more readily. What can your research tell us about the effective ways – and the not-so-effective ways – to talk about climate change with people who remain sceptical about it?

Q.: Your 2017 book ‘The Seasons Alter’ is in part an attempt to present the realities of global warming in a digestible way for the general public to understand the science and politics of climate change more readily. What can your research tell us about the effective ways – and the not-so-effective ways – to talk about climate change with people who remain sceptical about it?

P.K.: Our book imagined dialogues between an activist and a sceptic with respect to each of the six questions I mentioned earlier. It’s hard to say whether we succeeded in providing models for constructive conversations between members of these two parties. I’ve received a fair number of enthusiastic emails from readers who thought the book was a must-read for their sceptical friends. In retrospect, though, I’d have written the third chapter differently; the dialogue there didn’t probe deeply enough into the vulnerabilities many opponents of climate action feel. I think the participants should have been people who were actually seeking jobs (rather than people who had just found them), and that the difficulties of economic disruption should have been presented more deeply and more vividly.

Q.: In their 2012 book ‘Merchants of Doubt’, science historians Naomi Oreskes (who recently delivered a lecture as part of the PERITIA Lectures Series) and Erik M. Conway ring the alarm on ‘mercenary scientists’ – high-level scientists with strong ties to particular industries – who use their influence to “keep the controversy alive”, actively misleading the public by denying well-established scientific knowledge, including on climate change. How can experts and science communicators help the general public identify these ‘contrarian scientists’ and pinpoint their underlying motivations?

P.K.: As my review in Science indicated, I think Merchants of Doubt is an exceptionally important book – one of the greatest contributions to public understanding of climate change.

I would love to see greater transparency in how the money flows into science labs and into particular projects. I suspect (though I don’t know) that there are all sorts of barriers to getting the information. But, assuming those barriers were broken down, journalists would have a moral responsibility to recognise who is getting funding from Big Oil or Big Pharma, adjust their assessments of controversies accordingly, and let the public know which of the alleged “contrarians” are getting handsomely paid for their efforts. If journalists could find out how the funding flows, and then live up to their responsibilities, the result would be a great legacy of Oreskes’ and Conway’s pioneering work.

“I would love to see greater transparency in how the money flows into science labs and into particular projects. I suspect that there are all sorts of barriers to getting the information.”

Q.: Many news platforms – and even some science journals – like to talk about “both sides of the global warming debate” to seem more balanced and unbiased, presenting unsubstantiated alternatives as though they are on equal footing with the scientific consensus, which can make it harder for people to distil fact from fiction. At the same time, not mentioning such ‘alternative positions’ may lead some people to feel suspicious and think that certain facts are being hidden from the public. How should we address this paradox?

P.K.: I have been appalled by the tendency of many reputable newspapers to write articles that “balance the conflicting views.” Of course, doing that is just fine when a debate is genuinely unsettled. When a scientific community has reached a consensus, however, it’s either cowardice or a misguided effort to “make science exciting” and so woo, or retain, readers. A whole generation of science journalists seems to fear being sued, sacked or vilified if they take a firm stand. Their editors also appear to want them to emphasise the “personal aspects of the story” – as if readers wouldn’t read an article about science unless it were jazzed up. My guess is that the root of the problem lies with the sense, on the part of journalists and their bosses, that they don’t know enough about science to give their own assessments. That could be remedied if people with a strong background in science were actively recruited, if journalists were offered paid leaves to keep up to date, and so forth.

You are right to hold that people will protest that a newspaper, website, or news channel is “taking sides.” The trouble is that, in our epistemically fractured world, people already believe that about the media they are taught to despise. Getting back to a situation in which media don’t always tell their adherents what they think those people want to hear will be extremely hard.

“[Balancing conflicting views] is just fine when a debate is genuinely unsettled. When a scientific community has reached a consensus, however, it’s either cowardice or a misguided effort to ‘make science exciting.’”

Q.: What is your position on the argument that individual changes (e.g., reducing meat consumption, flying less, recycling more, etc.) are just as important as – some might argue even more important than – systemic changes (e.g., eliminating fossil fuel subsidies, introducing carbon pricing, etc.) in reducing our carbon footprint on the environment?

P.K.: Completely straightforward. It’s a good idea for individuals to do what they can. But they should realise that individual effort alone is never going to do the trick. Even if decisions by people began to create incentives sufficiently strong to outweigh the bribes producers currently get under the status quo, the process would be far too slow to do much good. Giving up meat is a good idea for at least two other reasons. Installing solar panels is a good idea, too. But without very large systemic changes, probably far more ambitious than anything any climate summit is likely to yield commitments to (let alone live up to), emissions will continue to accumulate at dangerous rates.

Q.: Renowned climate scientist Michael Mann has argued in his latest work that outright climate denialism is now fading, and in its place we are seeing what he describes as a new form of ‘soft denialism’, which ultimately has the same goal of slowing actions to curb CO2 emissions. Do you agree? If so, what do you think would be some effective strategies to combat this new form of soft denialism vis-a-vis the more traditionally overt forms of climate change denialism?

Michael Mann is a brilliant climate scientist, an excellent writer for the general public, and a brave man. He’s basically right. I’d just add that there are all sorts of forms of “soft denialism.” Some ex-sceptics say “It’s too late to do anything.” Others say “Why do we take the interest of people who have not yet been born more seriously than those of all the living people who are suffering?” Others might say “The best we can do for future generations is to keep the economy going.” Others say “This is a collective problem, and requires collective governance – but we’re never going to get that (a good thing too, nobody wants to be run by the UN or faceless bureaucrats in Brussels).” Yet others might say “What we need is geo-engineering. The current forms are either too risky (sulphur in the atmosphere) or only applicable at small scales (carbon capture). Let’s wait until technology discovers the solution.”

I could go on and on about this. We argue that the concerns of the living are important, but that they need to be balanced against our obligations to future generations. It cannot be a matter of ignoring either constituency. Similarly, rich nations, the countries that have created the current mess, have ethical obligations to parts of the world that would otherwise be denied the opportunities for economic development that the mess-makers have long enjoyed. Problems of collective actions have different scales at which all parties must come to agreement – and it is therefore foolish and irresponsible to retreat from joint deliberations, simply out of aversion to transnational entities (or faceless bureaucrats in different places). Finally, to do nothing, and bet on technology finding a way out is an irresponsible gamble on the human future.