Fighting for Sustainable Science – One Lab at a Time

Academic and research institutions play a key role in providing evidence on the climate crisis as well as potential mitigation strategies. But, what are they doing to become more sustainable themselves? ALLEA’s latest report Towards Climate Sustainability of the Academic System in Europe and beyond suggests that much more can, and should, be done to make the academic system climate-conscious and sustainable. A change in culture is required where all stakeholders within the academic system become aware of their climate impact and act to reduce it.

One focal point for such a culture shift within academia is the lab. Laboratories are integral spaces for research, innovation and technological progress. But they are also resource and energy intensive. One estimate found that labs account for about 2% of global public waste and use as much as 3 to 10 times more energy per square metre compared with a typical office.

What can labs do to reduce their climate impact? That is the very question Martin Farley has been working on in the last years. As the creator and manager of the Laboratory Efficiency Assessment Framework (LEAF) at the University College London (UCL), he has been doing this by creating and disseminating a green lab standard, and providing toolkits and resources to help scientific institutions improve the sustainability and efficiency of their laboratories. In this interview, we talk to Mr Farley, Europe’s first full-time sustainable laboratory specialist, to understand the challenges and opportunities in the quest to reduce the climate impact of labs.

“Sustainability as a topic of research and discussion will only grow, so I thought, ‘why not consider it in laboratories also?’”

Question: What motivated you to push for the sustainable transformation of scientific labs? Why did you focus on this particular niche?

Martin Farley: I worked and studied in labs in the US and Netherlands. During my time in these labs, I couldn’t help but notice the volume of plastic that I was using, particularly for tissue culturing (a research technique that involves growing animal or plant cells/tissues on an artificial medium outside the parent organism), and I wondered if anyone was doing anything about the sustainability of science. Sustainability as a topic of research and discussion will only grow, so I thought, “why not consider it in laboratories also?” It turns out that science facilities, while niche, are quite resource intensive with many opportunities for sustainability wins.

Q: Tell us a little bit about how you developed, and currently manage, UCL’s LEAF Programme. Was this an initiative that came from you? What barriers were the most challenging to overcome in the process of setting up the programme?

MF: While I initiated the programme, the support from UCL has been crucial to LEAF’s creation, particularly support from Joanna Marshall-Cook, Aaron Kashab, Vindya Dassanayake, Richard Jackson, and Ciaran Jebb, to name a few. Beyond the expected challenges one encounters when developing a new initiative, such as time, creating a website, or building engagement, I’m not sure there have been many that are notable. Both the scientific and sustainability communities have been hugely supportive of this effort, and LEAF has grown thanks to that support. I should add that we still have more to develop, and we need to find the best ways to expand LEAF’s remit while maintaining impact.

“We could also include sustainability and efficiency requirements, as we do with health and safety requirements, in the building and refurbishment of science facilities.”

Q: In a Nature article, you mention that the LEAF framework was developed to set shared standards for sustainable laboratories. Can this framework be applied across disciplines and geographical boundaries (we noticed that most of the signatories are in the UK)?

MF: While the majority of institutions that have signed up are from the UK, LEAF is in use in 14 countries now, including two institutions in Australia. This framework certainly can be applied beyond the UK. We’re also developing some new versions of LEAF for more specialist environments, which should be ready in early 2023 for participating institutions. The work that we’ve done has shown that there’s a lot of people working in specialist environments seeking guidance on how to be more sustainable.

Q: You also advocate for more stringent, mandatory “sustainability requirements” analogous to those for occupational safety. What could that look like?

MF: There’s much scope for discussion on what this would look like, but I like the health and safety model – having common, accessible standards that operations may be assessed against. Such standards in the sustainability space should be supported by academic institutions, funders, and commercial operations. We could also include sustainability and efficiency requirements, as we do with health and safety requirements, in the building and refurbishment of science facilities.

“I think more sharing and standardisation of approaches might be positive in our transition to climate sustainability. Currently, institutions need to […] repeat the same learnings that others have likely already done.”

Q: What are some of the challenges you have encountered with institutions trying to replicate the LEAF standard?

MF: I think generally most sustainability initiatives are voluntary, and so are dependent on the availability and willingness of individuals. This is a challenge for all such initiatives: How does one transition from a singular effort of goodwill to a common practice? My hope is LEAF helps them make that transition more easily, but it’s only one part of the wider sustainability efforts.

Q: Beyond laboratories, what would you like to see more/less of in the academic system’s transition towards climate sustainability? What are the low-hanging fruits that we can immediately build on right now?

MF: I think more sharing and standardisation of approaches might be positive in our transition to climate sustainability. Currently, institutions need to each develop their own strategies, create their own job descriptions, and repeat the same learnings that others have likely already done. I know academic institutions in some ways are in competition, but when it comes to sustainability, we need to understand that we’re on the same side. Sharing of practices does take place, but more could facilitate a quicker acceptance of targets, standards, etc. Also, there could be more efforts made to understand scope 3 carbon emissions (indirect emissions across an organisation’s whole value chain, such as travel, lab equipment, materials and waste) because by only focusing on scope 1 (direct emissions such as from refrigerants, on-site electricity generation and gas consumption for heating) and scope 2 (indirect emissions from energy directly consumed) emissions, we might be shooting ourselves in the foot. Low-hanging fruit might be as simple as shutting down our buildings (lights, heating etc.) after office hours.

“I know academic institutions in some ways are in competition, but when it comes to sustainability, we need to understand that we’re on the same side.”

Q: What institutional or cultural practices within academia are the most difficult to change in the transition towards climate sustainability?

MF: I think our accounting systems potentially disincentivise sustainability solutions. The financial year is 12 months, but sustainability planning might rely on much longer time scales, and this mismatch could create challenges for institutions to incorporate climate-conscious solutions. But we can work around these challenges. The budget to build a facility, for example, might be different from the one that pays to operate it. Equally, the individuals who utilise resources (like energy or consumables) often aren’t those who are responsible for paying for them, which affects consumption – bridging this gap between the payers and users could have a positive impact on consumption. I think we need to consider financial models and incentives alongside standards if we want to achieve some long-term net-zero goals.

Q: Do you believe that the sustainable transformation within academia is happening fast enough?

MF: I’m certainly encouraged enough to keep trying!

Martin Farley will be one of the panelists at the hybrid event Towards Climate Sustainability – Taking the Academic System from Evidence to Action on 2 November, co-organised by ALLEA in partnership with the Swiss Embassy in Berlin and Die Junge Akademie as part of 2022 Berlin Science Week. Learn more about this event here.

—

About Martin Farley

Martin Farley is the founder and manager of the Laboratory Efficiency Assessment Framework Programme (LEAF) at the University College London (UCL), as well as the Director of Green Lab Associates, a consultancy which helps make laboratories more efficient and sustainable.

While he began his career as a biologist, Farley went on to become the UK’s (and Europe’s) first full-time sustainable laboratory specialist at the University of Edinburgh. Today, his pioneering strategies are used by research universities in Europe, Australia, China, Singapore, and Japan to identify, track, and meet sustainability goals in the lab. Farley has been recognised for his innovative work in the sustainability sphere with the EAUC’s Sustainability Professional Green Gown award, as well as an Institute of Environmental Management & Assessment fellowship.

Recent Publications by Martin Farley

How green is your science? The race to make laboratories sustainable

Getting labs to net zero needs a coordinated effort

Re-use of labware reduces CO2 equivalent footprint and running costs in laboratories

The Academic System Is Not Exempt from Imperatives to Transition to Climate Sustainability

A new ALLEA report delves into academia’s impact on the climate through its own operations from the perspective of various stakeholders that play a key role in shaping the academic system. The report goes on to make a series of tailored recommendations to mitigate detrimental effects.

In a new report published today, ALLEA, the European Federation of Academies of Sciences and Humanities, examines the academic system’s negative impact on the climate through its own activities. The report takes a comprehensive outlook on the operations of various stakeholders and suggests that significant changes are necessary for the academic system to reach climate sustainability.

The report, prepared by ALLEA’s Working Group Climate Sustainability in the Academic System, stresses that in order for the academic system to transition to climate sustainability, “a change in culture is required, where individuals and institutions become aware of their climate impact and act to reduce it.”

The authors evaluate the operations of different actors that jointly set the standards and framework conditions of the academic system, namely Universities; Research Institutes; Students; Individual Academics; Funding Organisations; Conference Organisers; Ranking Agencies; Policy Makers; and Academies, Learned Societies and Professional Bodies.

By analysing available data on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the report shows that air travel is one of the major GHG contributors within academia, and therefore virtual interactions will be critical for the academic system to become more sustainable.

“We envision in-person, hybrid, hub-based and fully virtual events to coexist in the future, with a careful choice of format depending on the goals and participants of a given event,” the authors conclude.

The report also emphasises that other sources, such as supercomputing, buildings, electricity, and supply-chain emissions, may be equally or sometimes even more important emission sources than air travel, depending on the sector.

Finally, the report provides a series of best-practice examples and concrete recommendations that could lead to a significant reduction in the levels of GHG emissions that the academic system produces every year.

The report will be presented and discussed at the ALLEA General Assembly on 12 May 2022 in Brussels. Registration for onsite or online attendance is still open.

About this Report

This report has been prepared by ALLEA’s Working Group Climate Sustainability in the Academic System. Led by its member Die Junge Akademie (German Young Academy), the project lays out a proposal for a sustainable transformation of academia that is deliberated, balanced and accounts for all relevant perspectives such as to meet the challenge of a climate sustainable academia without leaving excellence in research behind and without diminishing international exchange and collaboration in academia.

Through its Working and Expert Groups, ALLEA provides input on behalf of European academies to pressing societal, scientific and science-policy debates and their underlying legislations. With its work, ALLEA seeks to ensure that science and research in Europe can excel and serve the interests of society.

Online Panel: Climate Sustainability in the Academic System

The ALLEA online panel ‘Climate Sustainability in the Academic System – the Why and the How’ provided a platform for discussion on the climate impact of the academic system and potential pathways towards more sustainable practices.

Panelists offered an overview of the current levels of CO2-equivalent emissions that can be tied to specific academic work. The discussion focused on the steps that universities, research centres, funding institutions as well as individual students and researchers can take to reduce their climate impact.

The online event, held on 1 February, was opened with a presentation by Professor Astrid Eichhorn, speaker of Die Junge Akademie and Chair of the ALLEA Working Group Climate Sustainability in the Academic System. Professor Eichhorn introduced the topic drawing from available research data as well as on some of the preliminary results from the upcoming report by the ALLEA Working Group.

Limiting Researchers’ CO2 budget

Professor Eichhorn set the stage to the discussion with an introduction to the data presented in the 2018 IPCC report, which estimated that there is a “remaining budget” of 420 gigatons of CO2-equivalent emissions for a 66% chance to stay below the 1.5°C of global warming stipulated in the Paris Agreement. This translates to a “budget” of 1.5 tons of CO2-equivalent emission per person per year. Data presented on the impact levels of universities, research institutes, and conference travels show that researchers from across scientific fields far exceed the yearly “budget” necessary to remain under 1.5°C of global warming.

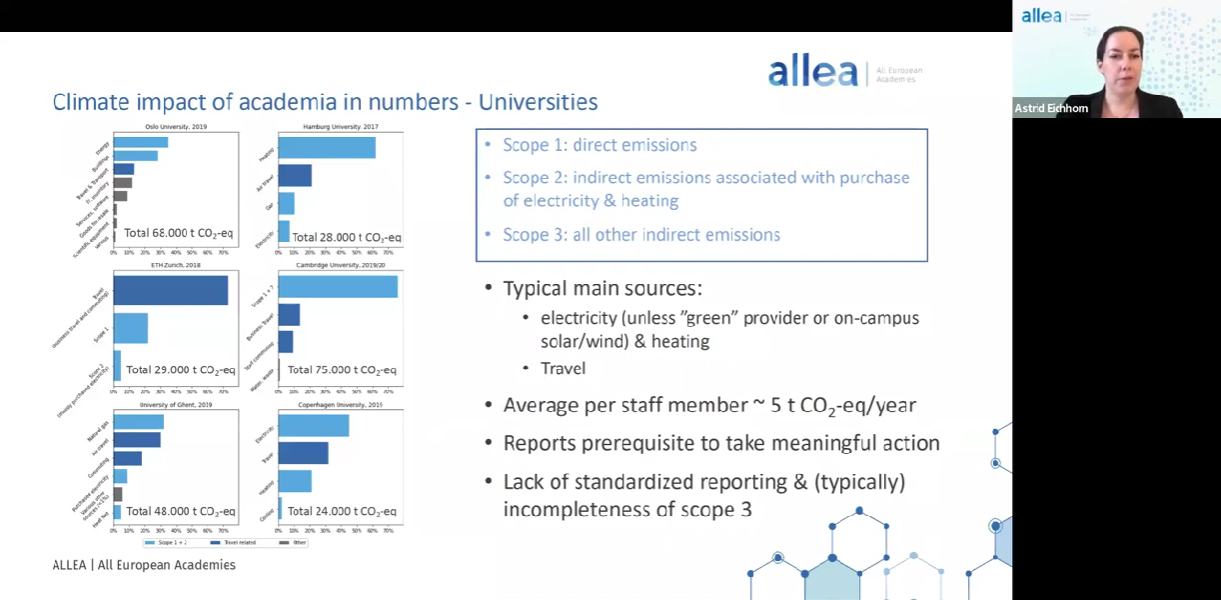

Universities

Some universities have managed to reduce their GHG emissions in electricity and heating by turning to “green” providers or by installing on-campus solar/wind energy sources

In regards to universities, Professor Eichhorn pointed out that the main sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions include electricity and heating, although some universities have managed to reduce their GHG emissions in electricity and heating by turning to “green” providers or by installing on-campus solar/wind energy sources. She also underlined that many universities are now starting to estimate and report their GHG emissions, which is a necessary first step to be able to take meaningful and tailored action against climate impact. However, comparing the different reports from universities reveals that there is still a lack of standardisation in reporting (i.e. different categories are being used and reported), which makes it difficult to compare across institutions.

Research Institutes

The main sources of GHG emissions at these institutions are very strongly tied to the research activities they perform

As an example for the level of GHG emissions from research institutes, Professor Eichhorn introduced the findings of a study from the Max Planck Institute of Astronomy in Germany, which estimates the CO2-equivalent emissions per researcher per year within the institute at 18.1 tons. In Australia, this number goes up to 41.8 tons per researcher per year, both digits being significantly above the previously mentioned “yearly budget” of 1.5 tons. A considerable fraction of emissions comes from flights, but also from electricity, of which a significant amount derive from the electricity used in scientific computing. The main sources of GHG emissions at these institutions are very strongly tied to the research activities they perform, which makes it challenging to reduce these emissions in ways that do not compromise the research quality.

Conference Travels

In-person conferences can reduce their GHG emissions by up to 20% by optimising the conference location.

Speaking on the climate impact of conference travels, Professor Eichhorn presented data estimating that the CO2-equivalent emissions per conference participant from air travel alone can be as high as 1 ton, with participants taking long-haul flights contributing to the larger share of emissions. She highlighted that switching to virtual meetings has the potential to bring about a reduction between 94% and 98% in GHG emissions compared to in-person meetings. In-person conferences can also reduce their GHG emissions by up to 20% by optimising the conference location. An additional co-benefit of virtual and hybrid events is the higher participation from students and researchers from traditionally underrepresented parts of the world, who usually cannot attend such conferences due to the distance or costs that this would incur. This higher inclusivity can also result in the increase of research quality.

Professor Eichhorn concluded by presenting data that show that an increasing number of individual actors within the academic system are taking a look at their climate impact and taking meaningful steps to reduce it. For instance, more than a 1,000 universities and colleges have made a net-zero pledge across different scopes. The Alliance of Science Organisations in Germany, comprising several research institutions, has pledged to reach climate neutrality by 2035, and there are also numerous initiatives to reduce flying in academia. However, Professor Eichhorn points out that it is necessary to go beyond initiatives by individual actors, but rather start thinking more systemically and initiate a broader dialogue with all of the stakeholders in academia to think about ways to make the academic system more climate sustainable.

Power Structures, Mobility and Academic Freedom

Following her presentation, Professor Eichhorn was joined by a panel of three experts: Dr Nina Marsh, Head of the staff unit Internal Audit & Sustainability Management at the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation; Professor Carly McLachlan, Director of Tyndall Manchester and Associate Director of the ESRC Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformation; and Henriette Stoeber, Policy Analyst at the European University Association’s Higher Education Policy Unit.

(Top-bottom, left-right) The panel was comprised by Dr Nina Marsh, Professor Astrid Eichhorn, Henriette Stoeber, and Professor Carly McLachlan.

Asked about one specific change urgently needed to make the academic system more sustainable, Professor Carly McLachlan spoke of the need for academics with more influence and power within the system to recognise and use their influence to change the current state of affairs within academia. This would entail, for example, a push to include climate sustainability in the requirements for academic promotions, research proposals, and other elements that are embedded within the academic career ladder.

There is a need for establishing criteria to make meetings in person or virtual and allowing for more flexibility for the mobility of researchers.

Speaking on the role of funding organisations in steering the academic system towards a more sustainable path, Dr Nina Marsh emphasised the changes that can be implemented in the area of mobility, particularly for globally-operating research networks that seek to facilitate inter-cultural exchanges. She pointed out alternatives being explored within the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation, including having criteria as to which meetings are required to be in person and which can be virtual, combining virtual and in-person meetings, and allowing for more flexibility in regards to mobility of research fellows. She also spoke on the need for such organisations to adopt ways to assess their environmental footprint in order to take more tailored steps to reduce their climate impact. Other stakeholders like service providers and organisational partners must also be taken into consideration when analysing the organisation’s climate impact.

Regarding the role of European higher education institutions in advancing climate sustainability in the academic system, Henriette Stoeber introduced a 2021 survey by the European University Association which comprised around 400 European universities. The survey revealed that an area where universities have been particularly active is the area of learning and teaching, for example by revising their curricula and including the topic of sustainability into their courses. In terms of net-zero targets, such as greening university campuses, infrastructure, and research activities, the data shows that universities’ strategies remain much less clear.

Asked about the impact of imposing more climate sustainable regulations on research and academic freedom, all panellists agreed that requiring research to be more climate-sustainable would not negatively impact the outcome of the research findings. Professor McLachlan asserted that academic freedom is about freedom of thought and freedom to explore the conclusions drawn based on the evidence. She emphasised that there are already restrictions and regulations in place to protect colleagues, research subjects and institutions. Protecting the environment and the people around the world, she argued, would be an extension of those regulations that are already in place.

The panelists concluded that it is not important to get everything right from the beginning, but what is important is that organisations and individuals commit to doing what they can to move towards climate sustainability. As individuals start to reassemble and move away from the pandemic restrictions, there is an opportunity to do things differently.

The panel was followed by an interactive session in which participants were able to join different thematic groups to continue the discussion. The thematic breakout sessions included Universities & University Networks, Students & Individual Researchers, and Funding Organisations. The breakout sessions were led by members of the ALLEA Working Group on Climate Sustainability in the Academic System.

Download Professor Astrid Eichhorn’s presentation