Q: What first got you interested in working with Digital Humanities?

Maciej Maryl: My background is in sociology and literary studies, which I combine in my research in the sociology of literature. I have always been interested in how technology reshapes the way we read and perceive culture, which was the topic of my doctoral dissertation. While working on it, I had a chance to learn digital methods from the late Prof David S Miall at the University of Alberta and Max Louwerse, then a professor at the Institute of Intelligent Systems at the University of Memphis. Right after obtaining my PhD, I was tasked with establishing the Digital Humanities Centre at the Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences, which federated and coordinated scattered digital initiatives of the Institute and provided a fruitful ground for the new ones.

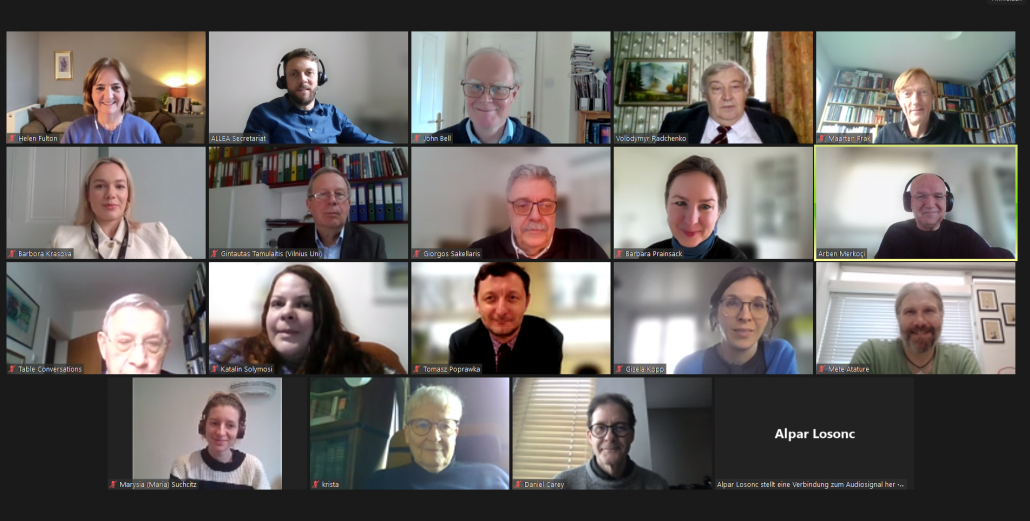

Q: Why is it important for you to participate in initiatives such as OPERAS and the ALLEA E-Humanities Working group?

MM: Work for the ALLEA Working Group is special because of the unique place of academies in the humanities, where they are usually tasked with long-term, monumental projects like scholarly editions, lexicons, biographies, or bibliographies. The E-Humanities Working Group aims to guide academies concerning new methods and opportunities while taking into consideration their specificity. We want to ensure that humanities research remains aligned with FAIR principles, i.e., research data is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable.

“We want to ensure that humanities research remains aligned with FAIR principles, i.e. research data is findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable.”

Q: How are advancements in data science methodologies such as Machine Learning systems enhancing Humanities research? On the other hand, what are the key obstacles to incorporating new technologies into humanities research?

MM: Digital humanities have long employed Machine Learning techniques in textual analysis or data mining. Studies of authorship attribution or recognising entities in texts are all based on such methods. To describe the use of such methods, we employ the term “distant reading”, which – as opposed to close reading of individual texts – expands a singular perspective and allows for the analysis of vast textual resources. However, these methods require interdisciplinary knowledge and data, namely corpora of texts, which are not readily available due to copyright restrictions. This underscores the importance of researchers making their data available so others can compile and use them in new projects.

Q: What was the primary aim of the new ALLEA report, ‘Recognising Digital Scholarly Outputs in the Humanities’?

MM: The report corresponds with our mission, as mentioned earlier, of making digital humanities more accessible to the academies. In this case, it is a natural follow-up or sequel to our previous report, Sustainable and FAIR Data Sharing in the Humanities, which discusses in detail the handling of humanities research data. However, we cannot expect scholars to engage with data sharing and digital practices when they receive credit only for traditional publications like journals and monographs. So, in the present report, we pave the way for recognition of such work.

Q: What would you say are the three main takeaways from the report?

MM: Well, first off, we posit that the digital is the new norm: the report highlights how digital tools and methods are changing the humanities, and digital technology is becoming essential for modern research in fields like history, languages, or arts. Secondly, scholarly work assumes new forms and formats which are better suited for digital data we are working with. The report highlights that digital projects, databases, platforms, and even software can be treated as valuable scholarly work, not just books and articles. Finally, the report argues that all forms of scholarly work, especially digital ones, need proper recognition and credit, just like any other important contribution to knowledge and culture.

Q: The report highlights the “ambiguous status of digital technologies in academia”. What are the primary barriers hindering their recognition within academic circles?

Q: The report highlights shortcomings in current authorship attribution schemes, where diverse contributions are often overlooked as invisible labour, especially evident in Open-Ended inputs aimed at enhancing published work. How do you propose addressing these challenges to foster a more equitable and collaborative research environment?

MM: In the humanities, we still tend to think about authorship in singular terms, and the range of credited contributions boils down to a handful: author, editor, maybe translator. People doing other work, which has become increasingly more important, like coding, data collection, cleaning, or annotation, are merely mentioned in acknowledgements or footnotes. In the best-case scenarios, they could be artificially added as co-authors, which does not reflect the specificity of their actual contribution. We need to use existing taxonomies to appropriately describe the individual’s contribution to the paper so they can receive proper recognition featured in their track record. Such descriptions may sometimes resemble movie credits, but this is the level of detail that is fair to everyone involved.

“We need to use existing taxonomies to appropriately describe the individual’s contribution to the paper, so they can receive proper recognition featured in their track record.”

Q: As a follow-up, how can we adapt evaluation systems to effectively recognise and accommodate the complexities of collective authorship in digital scholarly outputs?

MM: We should align evaluation systems with the wide range of academic contributions, not only focusing on authorship of publications (which are, of course, very important) but also considering the various ways individuals contribute to the scholarly community. The practical aspect of such evaluation is currently under discussion within the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA), with a very active contribution from ALLEA.

Q: According to the report, practices in the humanities, particularly around research assessment, “should evolve to keep pace with digitisation”. Which emerging trends could have a transformative impact on the way scholars in the humanities conduct research and disseminate their findings in the future?

MM: I believe we need to support innovative work wherever it fully leverages digital technology to enhance scholarly arguments. In the report, we discuss the Journal of Digital History as a case study. It serves as a great example of how to incorporate different layers of scholarly argument into one output, including scholarly narrative, methodology, and data. Evaluation practices should evolve not only to recognise such work as scholarly output but also to acknowledge the range of contributions from various collaborators. It appears that such work not only improves scholarly communication by aligning it better with the topic and method of research but also facilitates reader engagement with specific methods and data, enabling their reuse or replication of the study.

Q: What would you say are three actions academia can implement in a fairly short time that would have a big ROI in moving the humanities into the digital age, i.e., what are some low-hanging fruits we can address right now?

MM: To recognise the potential of digital tools and methods for the humanities, academia could focus on three general actions. Firstly, we need to ensure that data for digital research is readily available in standardised formats. Hence, we not only need to prioritise the digital collection and preservation of texts, images, recordings, and other types of data but also ensure they are accessible according to the FAIR principles. Our previous report focused on this aspect.

Secondly, we need to establish digital humanities centres within academies to foster interdisciplinary hubs that combine digital technology with humanities scholarship, enabling innovation and collaboration. The Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage (ACDH-CH) at the Austrian Academy of Sciences is a perfect example of employing digital methods in pursuing traditional goals of academies.

Finally, we should integrate digital tools and methods of social sciences into humanities curricula not only to broaden the scope of future research but also to provide students with tools allowing for critical scrutiny of other digital humanities outputs. Access to materials, tools, and competencies will form a good basis for digital humanities to flourish.

“We need to establish digital humanities centers within academies to foster interdisciplinary hubs that combine digital technology with humanities scholarship. Finally, we should integrate digital tools and methods of social sciences into humanities curricula.”

This interview is part of the ALLEA Digital Salon Series. The published report ‘Recognising Digital Scholarly Outputs in the Humanities‘ provides extensive insights on improving transparency in linking resources, re-evaluating authorship norms, and enhancing digital competencies for scholarly outputs.

About Maciej Maryl

Read more by Maciej Maryl